Emily Sachar

Grant awarded Spring 2016

Jared French: Investigating Homosexual Iconography

A MA Art History Project by Emily Sachar

Candidate for MA in Art History 2017

Supported by the Kossack Grant

American Artist Jared French is a little-known, understudied American artist who worked at the middle of the 20th century. He offered no interviews during his lifetime and issued only two brief statements about his work. Only two small retrospectives of his work have been mounted. Nonetheless, several major museums hold paintings by Jared French, among them the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

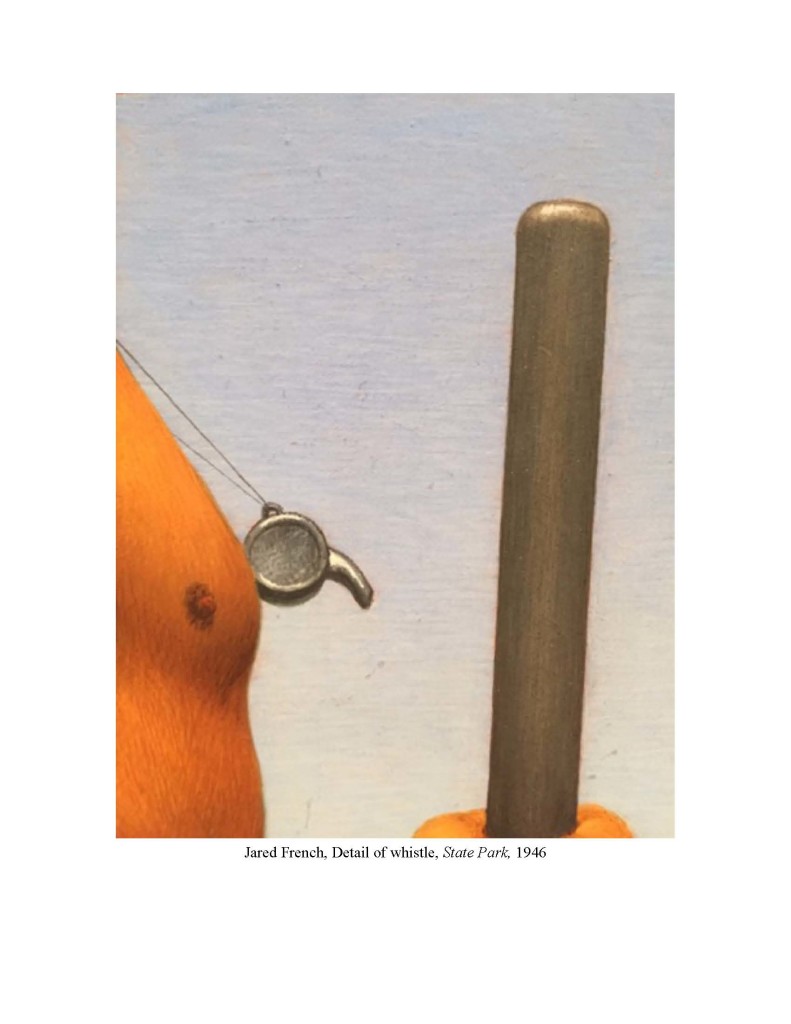

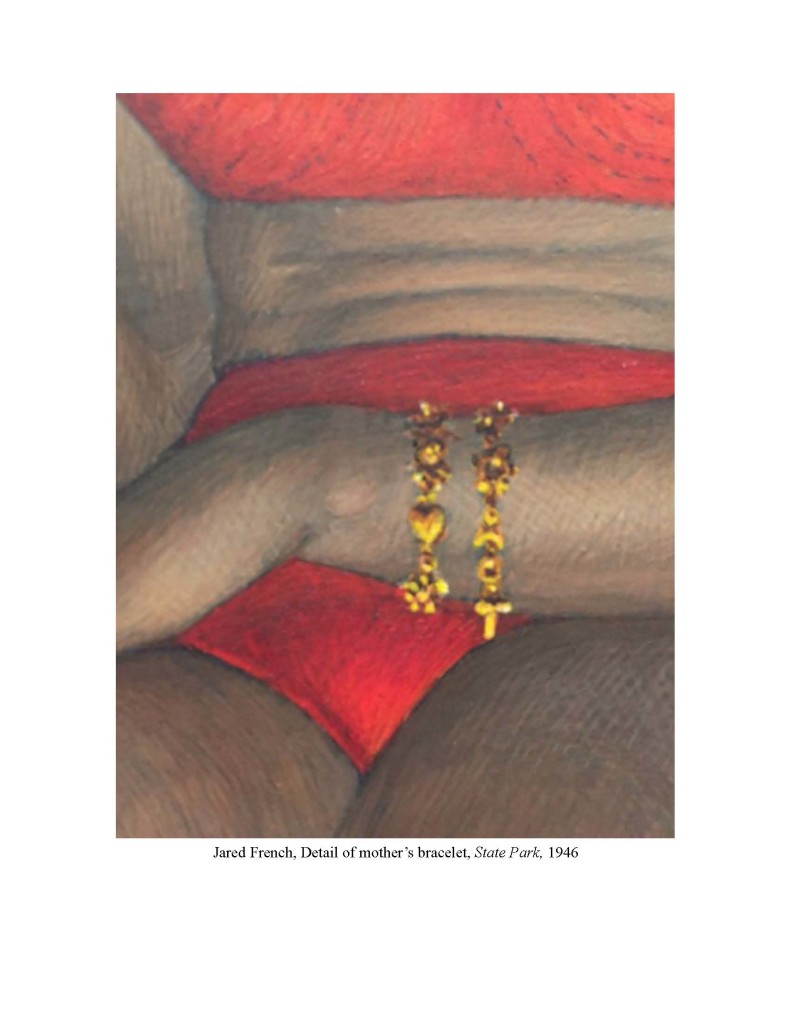

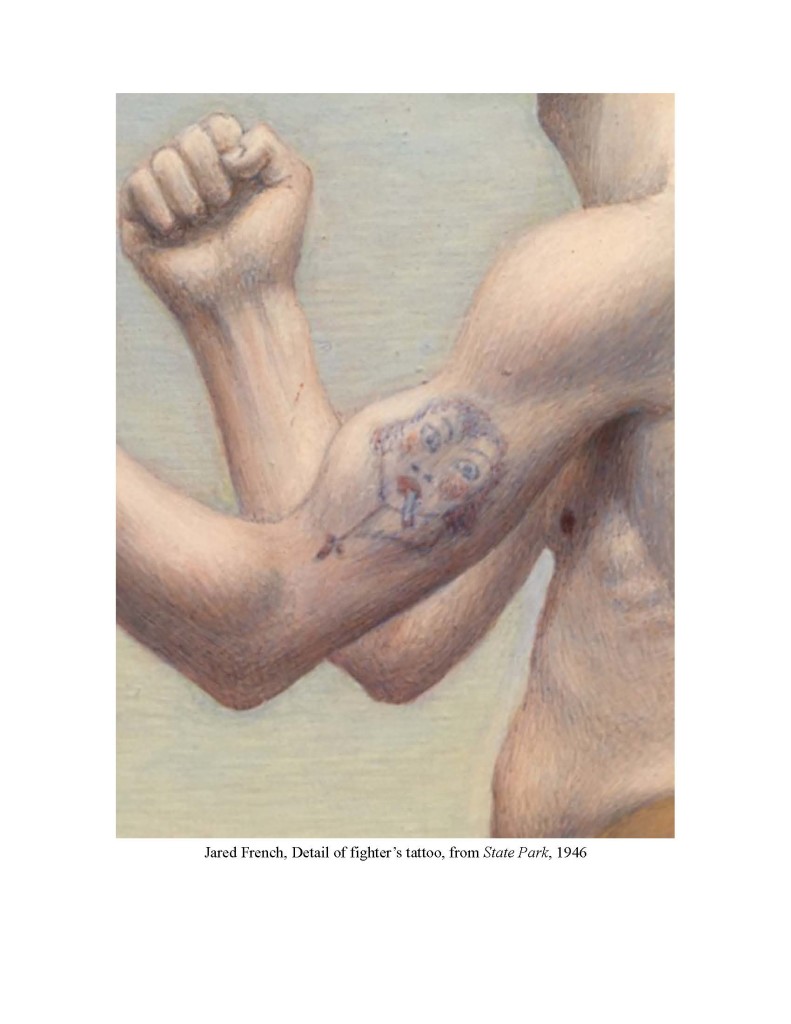

At the heart of my MA thesis work is an essential research question: In what ways is the work of Jared French populated with codes intended to signal his homosexual inclination to a knowing audience? I developed this question while examining one of French’s most well-known works, State Park (1946), at the Whitney for a Research Methods course. Magnification of several passages in this work indicate a phallic symbol charm on a bracelet, a tattoo on the biceps of a pugilistic figure in the background, and several other unmistakable allusions to homosexual proclivities (French was married, but had a longstanding love affair with Paul Cadmus, another mid-century artist).

As an art historian, I have considered it imperative to understand when French first began to use allusive symbols and codes and to examine at close hand several works in which the symbols asserting homosexual interests are nearly invisible to the naked eye. This required visits to American museums and the taking of photographs that could be enlarged for close study – techniques that proved ineffective, and in other ways impossible, with Google image searches.

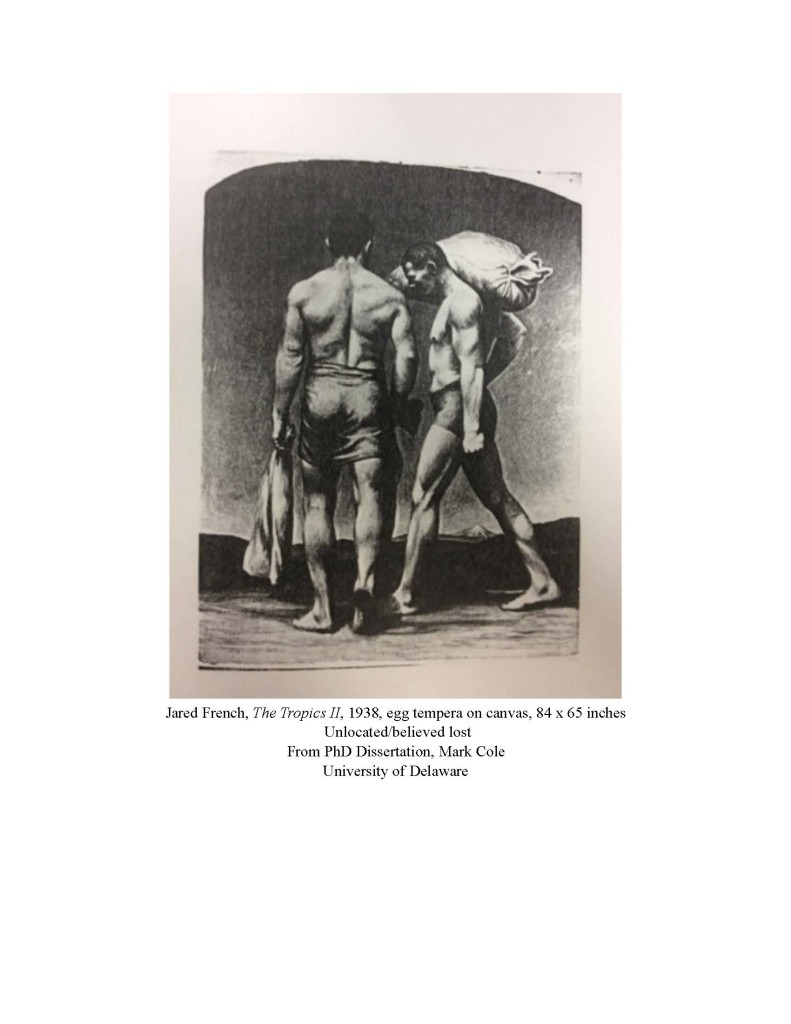

With my Kossak grant funds, I journeyed first to the University of Delaware to examine images of French’s work, albeit in black-and-white, in the 1980 PhD dissertation of Mark Cole; these were not accessible through PhD publishing channels because of copyright restrictions. I then visited Richmond, Virginia and Coxsackie, Pennsylvania to study two mid-1930s murals by French artist. Next, I journeyed to Cooperstown, New York to see an early work of a baseball player that evinces French’s work in the male physique in sports projects. And I concluded my travel with a trip to Cleveland to see French’s masterpiece, Evasion (1946).

The grant was essential to my research. I was able to determine with certainty that French’s fascination with painterly depiction of the male physique was in play during his work for several extant WPA mural projects and that it eventually morphed into a more subtle, but still forceful, crafting of his work in the 1940s.

Several images below illustrate some of the key themes French developed that bear out his interest in the male physique at a time when homosexuality was anathema and, in some parts of the United States, illegal.