Susie Sofranko

Grant awarded Spring 2016

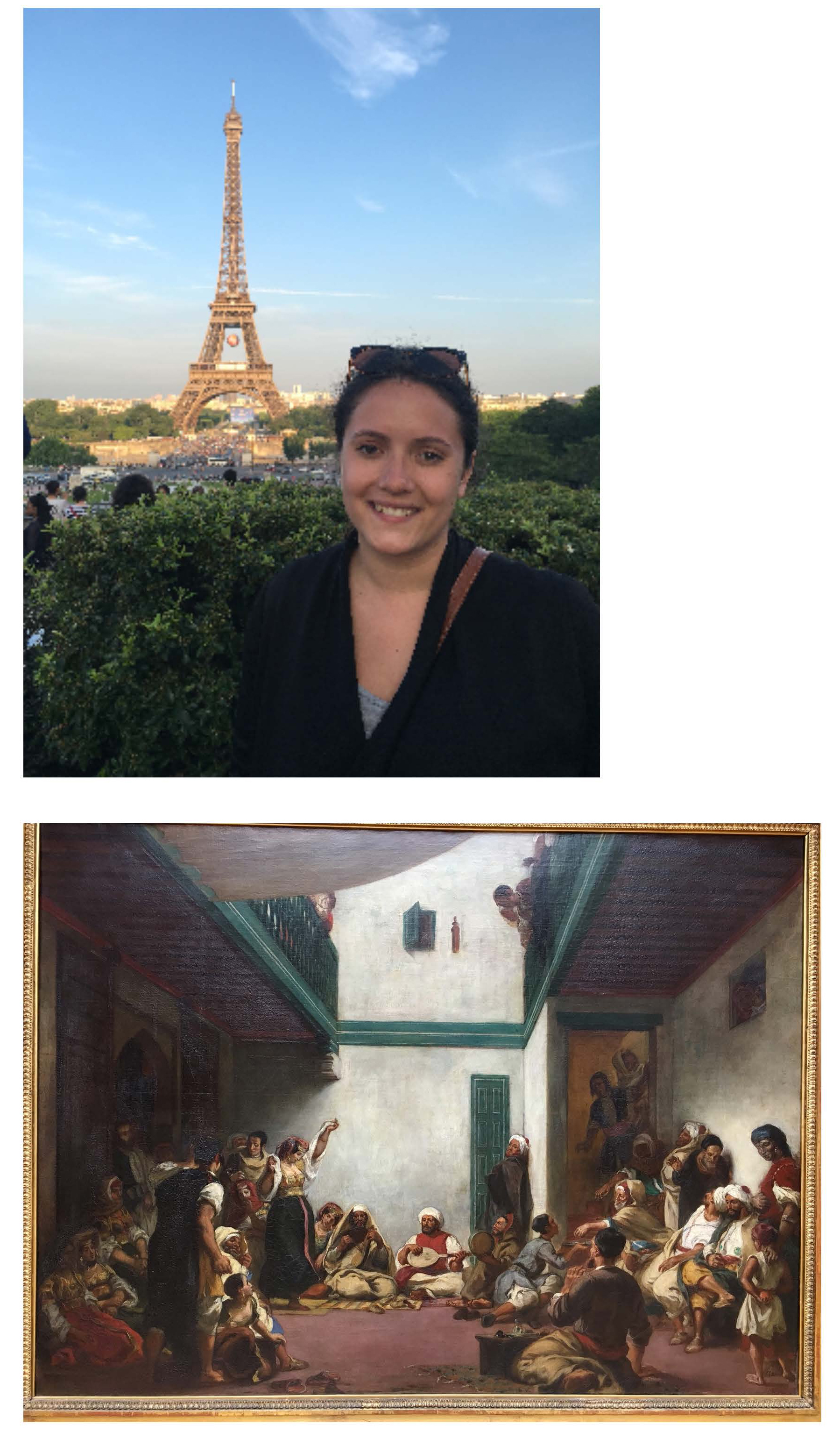

I traveled to Paris and Madrid last summer to undertake preliminary research for my senior thesis project that focuses on Spanish Orientalism. The overall objective was to hone in on a specific aspect of this subject by exploring the connections between Spain, France, and Northern Africa within painting and prints in various collections in Paris and Madrid, in order to discover works and formulate ideas to include in my thesis. I was looking for images that could be considered “Orientalist” and analyzing how images of Northern Africa differ from Spain and France. It was important to visit these places in person to discover works by artists that are less known outside of their respective countries.

In Paris I explored the genre of Orientalism that was in vogue in France in the 19th Century. This part of my trip was important because Paris, the center of the art world at this time, created and set the standards for Orientalism. Interestingly, many of the French Orientalists never traveled to the places the people they were depicting inhabited, so it was very much an imagined genre of the “other.” A prime example of an artist who never traveled to the East, is Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and his Grand Odalisque, one of the canonical Orientalist works at the Louvre. Also at the Louvre is Antoine-Jean Gros’ Napoleon Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken in Jaffa, as well as many depictions of oriental subjects by Eugene Delacroix. Delacroix actually did in fact visit Northern Africa, so while not all French Orientalist worked entirely from the imagination, his depictions played into that idea of exoticism and established the canon of French Orientalism. I explored this further at the Musee Delacroix where I stumbled upon some of his prints. The print making medium is especially interesting when considering its circulation across Europe because sure his Delacroix’s prints reached Spain and influenced Spanish Orientalism.

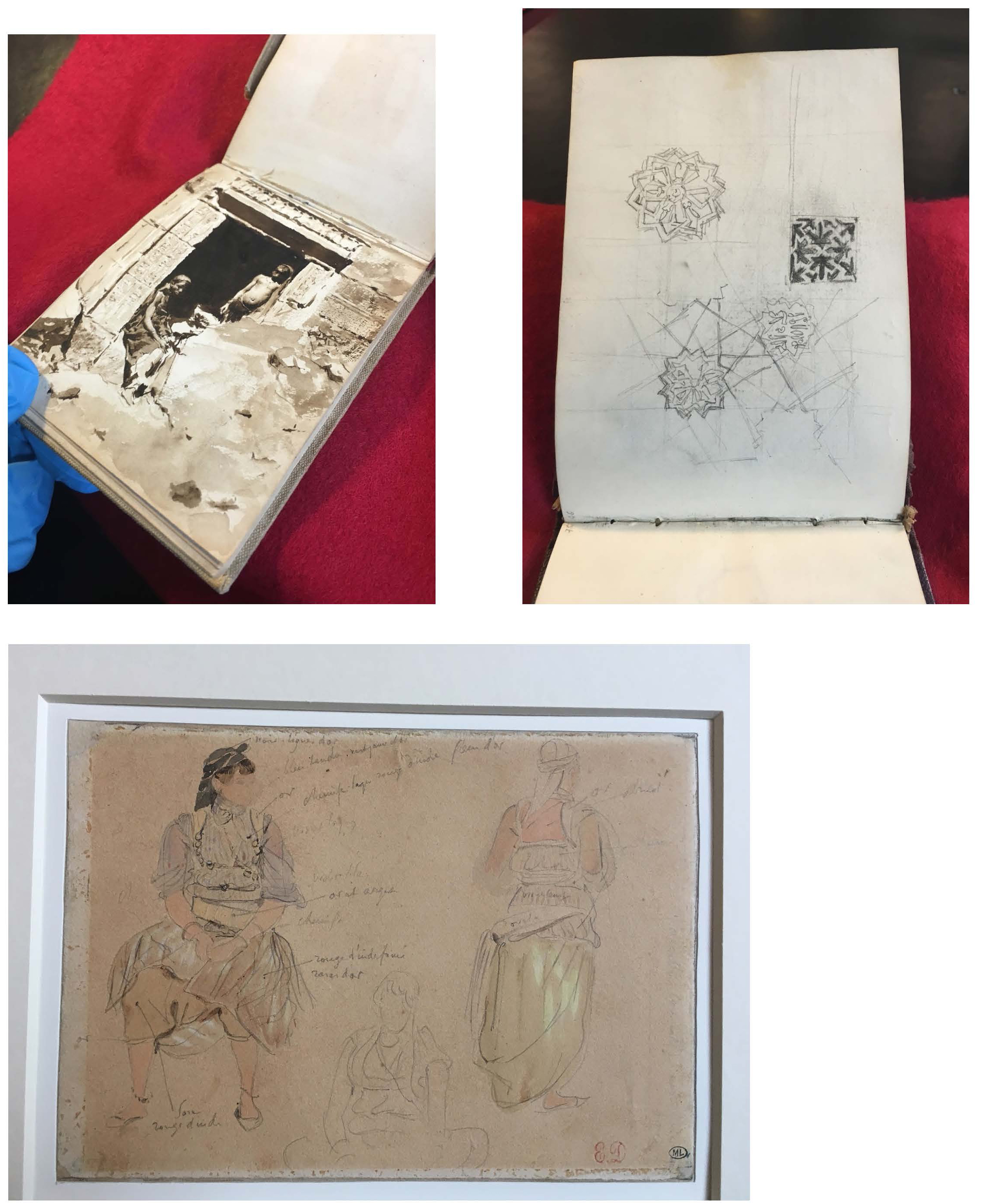

Another amazing opportunity I had in Paris was to go behind the scenes at the museums and see things that wouldn’t necessarily be on view. At the Musee d’Orsay, while there were more Orientalist paintings by Delacroix on display, I was invited to explore their archives where I found an article written by NYU Professor Edward J. Sullivan very relevant to my topic, which is going to be a huge resource for my thesis. I also had the amazing opportunity to go to the Drawings Department at the Louvre, where I looked at the sketches of Delacroix and Mariano Fortuny and was able to compare their respective ways of studying Northern Africa. Both artists went to Northern Africa in person, but you can see in their drawings they had very different approaches to their studies. Delacroix, for example, focused primarily on costume and color. He labeled the colors of dress showing that his primary intention was to display the vibrancy of his oriental subjects. This is very fitting considering the way Orientalism in France was so attached to material culture and the objectification of subjects and consumption of their exoticness. To the contrary, Fortuny’s studies focused primarily on architecture and very up close depictions of Moroccan subjects. There is something much more human about his drawings, and his focus on architecture speaks to the Moorish architectural past present across southern Spain.

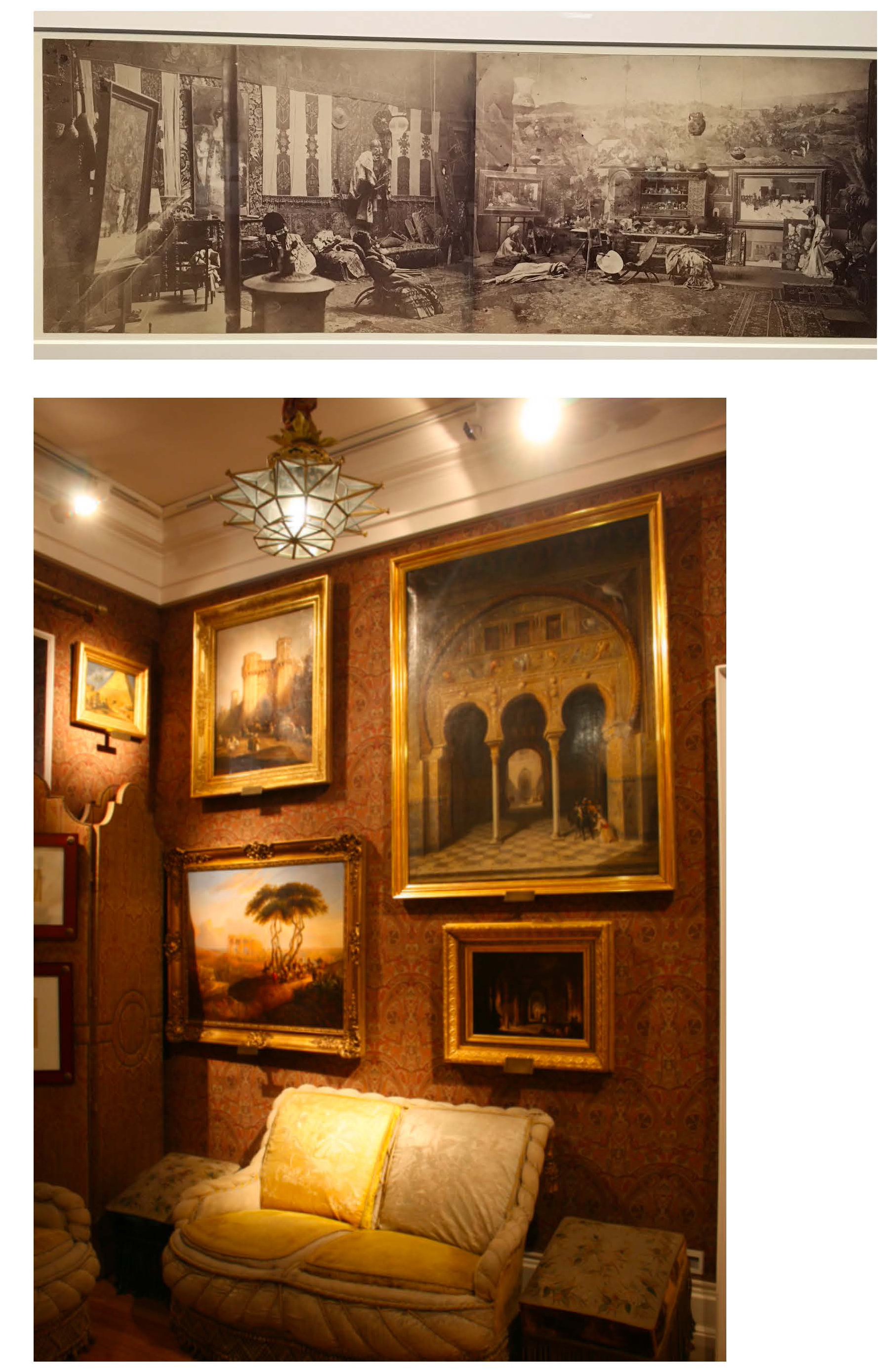

One final exhibition I stumbled up on in Paris was at the Petit Palais and focused on photographs of the artist’s studio and I was fortunate to find several of Fortuny’s studio on display. While Fortuny went to North Africa and studied the subjects on such an intimate level, these photographs show how he was also very much involved, even as a Spanish artist, in the French way of constructing the “other” right in his studio with the use of models and creating scenes of the East with a focus on sumptuous materials. Fortuny perfectly encapsulates an artist caught between the attractive trends coming out of Paris and his own identity as Spanish.

In Madrid, the most successful part of my trip was discovering the lesser known artists represented at the Prado and even more so in the smaller museums such as the Museo Lázaro Galdiano, the Museo Romanticismo, and the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. At the Prado there is an entire room dedicated to Mariano Fortuny’s work, such as the Battle of Wad Ras and “Morrocans,” but I was also introduced to the Spanish Romantics, many of whom I would later find to have participated in Spanish Orientalism as well. The Lazaro Galdiano, a house museum displaying the collection of a wealthy art patron from the early 20th century, had a collection deeply rooted in Spanish nationalism and celebrated many of the artists who are important to the Spanish but less known to audiences outside of the country. Francisco Lameyer, Eugenio Lucas Velazquez, and Eugenio Lucas Villamil, were Spanish Romantics important to the building of Spanish national identity through the depiction of landscapes and genre scenes, and like Fortuny, also painted oriental subjects in the French style. These Spanish Romantics were also highly represented at the Museo Romanticismo, and the Romantic connection to Orientalism was even clearer. For example, there was a “Smoking Room” intended as a place of sleepiness and well-being, and to evoke the sense of an exotic escape, it was decorated with Arabic motifs and Orientalist drawings and paintings. The room, described as a symbol of the masculinization of social life, was, to me, a prime example of Spain’s appropriation of the Parisian view, and use of, the Orientalist subject. The Spanish Orientalists were clearly painting in the French style, but they were also aware of their unique connection to Northern Africa. At Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, I stumbled upon an exhibition of Spanish draftsman from the late 18th and early 19th century, such as Juan de Villanueva, Diego Sanchez Sarabia, and Jose Maria Avrial y Florez, depicting Moorish architecture in Southern Spain. I believe this relationship to the architecture of Northern Africa represents the departure of Spanish orientalism from French orientalism, and this is an idea I plan to activate in my thesis.

As I have overviewed, physically being in Paris and Madrid gave me the opportunity to find works of art that I wouldn’t have discovered had I done this research from the US. So much of the fruitful material I discovered on this trip, were things that I stumbled upon, rather than had planned to see. And just as important was the opportunity to experience the respective cultures, especially because my topic – while set in the 19th century – is something that resonates to the current day. The subject of the bullfight, for example, is highly prevalent in Spanish and French art as well as a subject of debate in the 19th Century. The debate is that the bullfight as an integral part of Spanish society creates a barbaric image of Spain, yet others celebrate this history of “Spanishness.” Arguably, French artists depicting the Spanish bullfight in the 19th Century takes on another form of Orientalism, showing the “otherness” of a culture and highlighting superiority and inferiority between cultures. I went to a bullfight in Spain and talked to Spanish locals about the bullfight debate that is still very relevant today, and this was very telling of how Orientalism in the 19th Century can continue to shed light on cultures and their feelings towards other cultures today.

I can’t thank the Kossak family and Hunter College Art Department enough for giving me this amazing opportunity. The research I acquired on this trip will be an absolutely integral part of my thesis.