Tatiana Mouarbes

Grant awarded Spring 2015

In June of 2015, I traveled to Lebanon with the support of the Kossak Travel Grant, embarking on a two-week research trip throughout the country. The purpose of my trip was twofold: first, to see examples of recent paintings by Beirut-based artists in situ and second, to research the discourse on painting in Lebanon through an examination of critical, historical, and archival material. Specifically, my goal was to analyze the role of painting as it relates to larger narratives of contemporary art production in Beirut, which is so often categorically associated with video, photographic, and conceptual art practices. I visited the “Gallery 3010” exhibition at Sfeir-Semler Gallery and consulted the archives of Ashkal Alwan: The Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts and Beirut Art Center. Emphasis was placed on these three institutions in particular, as each have played a vital role in establishing infrastructures for art and arts education in Beirut and in forming a critical contemporary art scene, in both the for-profit and non-profit sectors.

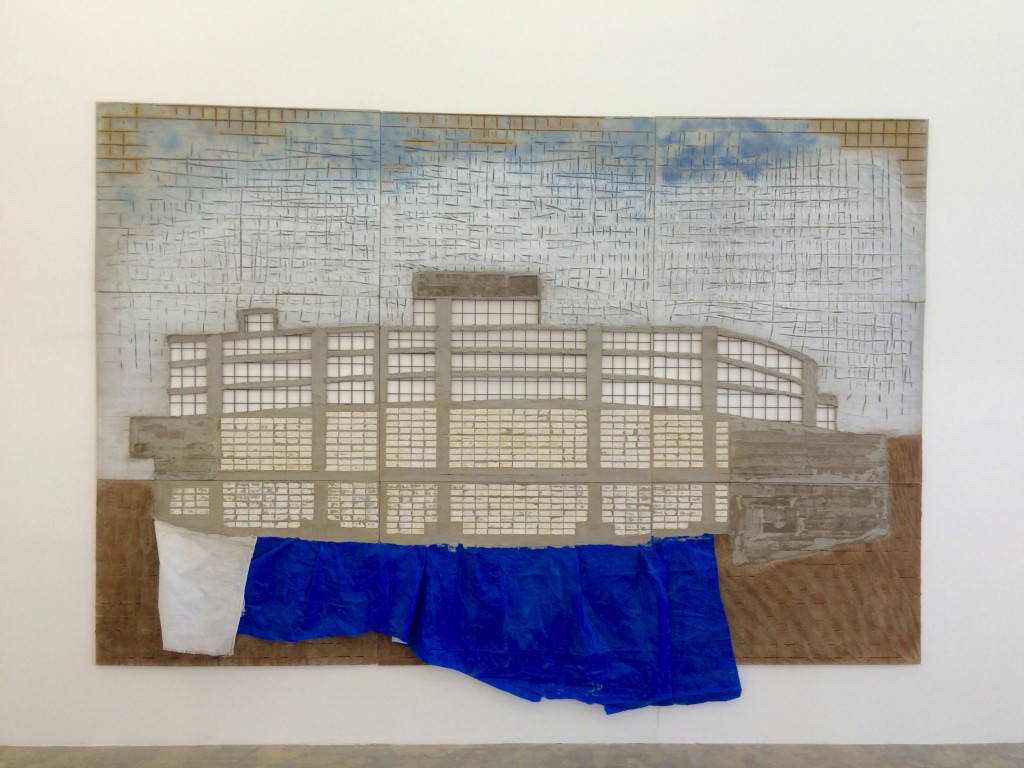

At Sfeir-Semler, I saw a series of paintings by artists Etel Adnan, Anna Boghiguian, Khalil Rabah, and Marwan Rechmaoui included in “Gallery 3010”. The exhibition, organized on the occasion of the gallery’s ten-year anniversary in Beirut, explored the concept of the “white cube gallery” and its mechanisms of installation and exhibition making, while looking back on the gallery’s history as a space for contemporary art in the city. In each of the works in question, the artists engaged a degree of self-reflexivity, either in referencing painting’s institutional function or its locational function within the context of Beirut. This impulse is best emphasized in the paintings of Rabah and Rechmaoui. In Rabah’s Art Exhibition, (2011) the artist displays a series of small and large-scale oil paintings suspended within sliding metal storage racks. In a gesture of mimetic play, Rabah’s paintings depict scenes of visitors, artists, and cultural workers interacting with artworks in institutional spaces for art, while installing the works as they would appear in a museum storage room. Rechmaoui’s Untitled, (2015), a mural sized mixed-media painting made with concrete, plastic, and paint, makes use of those materials used in the construction of the city and represents the in-between aspects of Beirut’s built environment, a city that has experienced a series of destructions and reconstructions since the end of the Civil War in 1990.

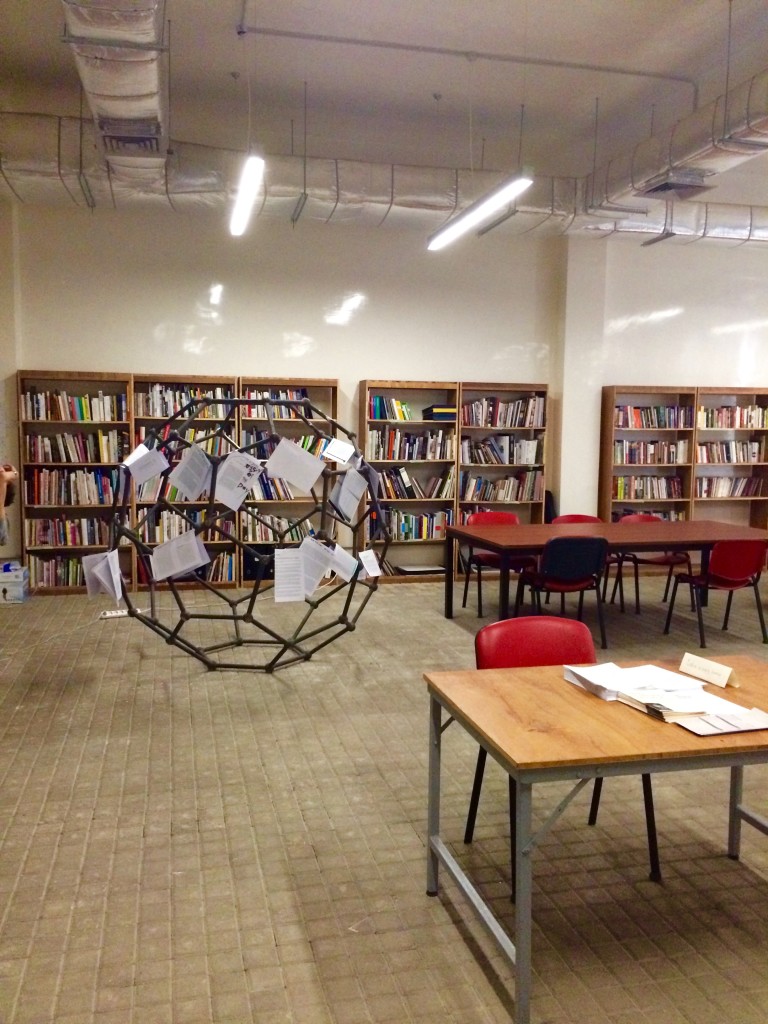

Much of my time was spent in the libraries of neighboring institutions Ashkal Alwan and Beirut Art Center, reviewing press releases, exhibition catalogues, scholarly and journalistic articles, dissertations, theses, and books on contemporary art in Lebanon as well as photographic and video documentation of performances, exhibitions, and art events in Beirut. Through this analysis, a clear, dominant narrative of contemporary art in Beirut emerged; one that privileged a history of artists and artworks working in experimental and ephemeral means, conceived as collective, self-organizing, and (somehow) removed from the market. Within this configuration, painting and sculpture were either relegated to the past or to the market – in both cases, stripped of conceptual or critical import. I came to see this simple formulation as symptomatic of a boarder discursive effort to build a framework for contemporary art in Beirut, privileging particular narratives and strands of artistic production while creating false and reductive binaries of form and content. Viewing paintings at Sfeir-Semler Gallery and gathering historical and archival material from Ashkal Alwan and Beirut Art Center greatly enhanced my research, providing grounds to complicate this history of art production and its overarching narrative.