Danielle Peterson Searls

Grant awarded Spring 2014

Thanks to the generous funding of the Kossak Travel Grant I was able to travel to Spanish Catalonia and Switzerland to do research on medieval artistic exchange between the Islamic world and Latin West. The focus of my academic work is textiles and on this trip I saw literally hundreds of examples of works that have not been published but are relevant to my research.

The Abegg-Stiftung in Riggisberg, Switzerland, had an important exhibition on view called “Veil and Adornment: Medieval Textiles and the Cult of Relics”: the first-ever exhibition on the topic of textiles associated with medieval reliquaries and the cult of the saints. This was relevant for my work at Hunter as I am writing a thesis on the Veil of St. Anne, an 11th-century Fatimid textile that was brought back from the Crusades as a holy relic of Anne, the mother of the Virgin. In coursework I have been able to form a theoretical framework for my thesis, but the visit to the Abegg Foundation was essential.

Tucked away in the Swiss Alps, amid fields of cow pastures, is the Abegg, which houses the world’s finest collection of textiles as well as a cutting-edge laboratory and research center. The staff there was extraordinarily welcoming and I was able to amass a great deal of technical and historical information and research leads in their library. However, it was the opportunity to see so many examples of the actual medieval textiles that was so important for my work. I was able to get a sense of their physicality, scale, and, what surprised me most, optical effects. These rare, millennia-old, and newly restored silks shimmered like jewels and seemed to emanate light. Seeing them gave validity to the medieval first-hand accounts (both western and Islamic) that describe the textiles with such a sense of bedazzlement.

In Zurich, I also saw Sigmar Polke’s stained glass windows at the Grossmünster, and in Bern I visited the Kunsthalle, the site of so many important 20th-century exhibitions and works. Both sites fueled my interest in exploring the affinities between medieval and modern art and offered a valuable contraposition to the 12th-century works that are the focus of my research.

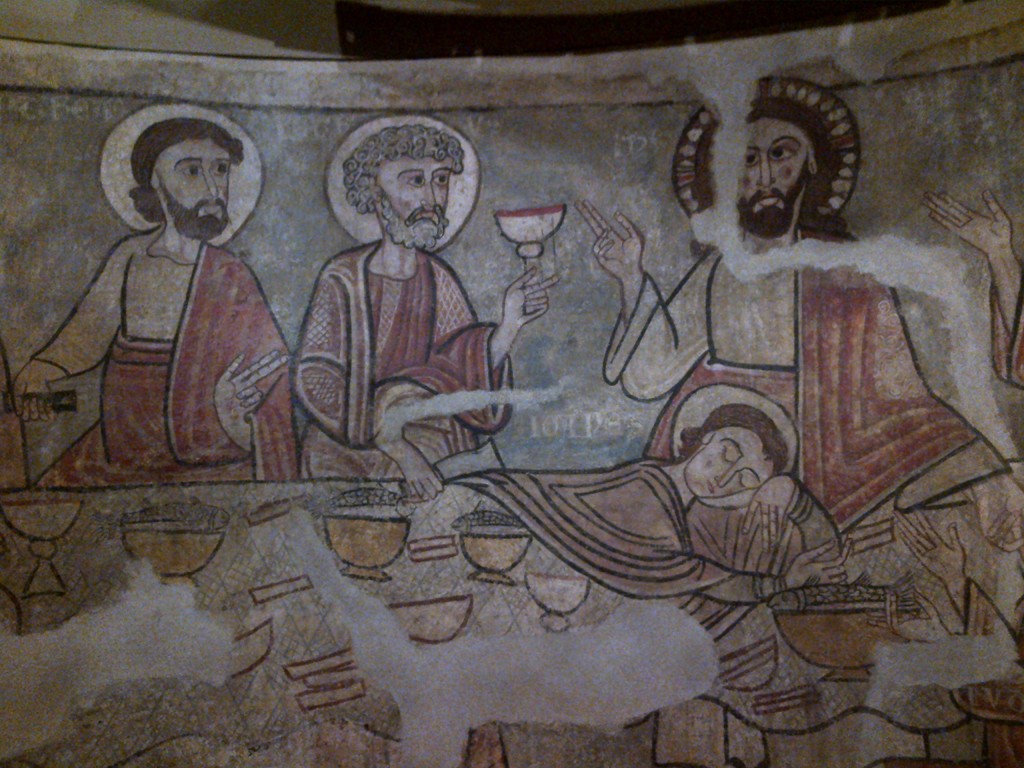

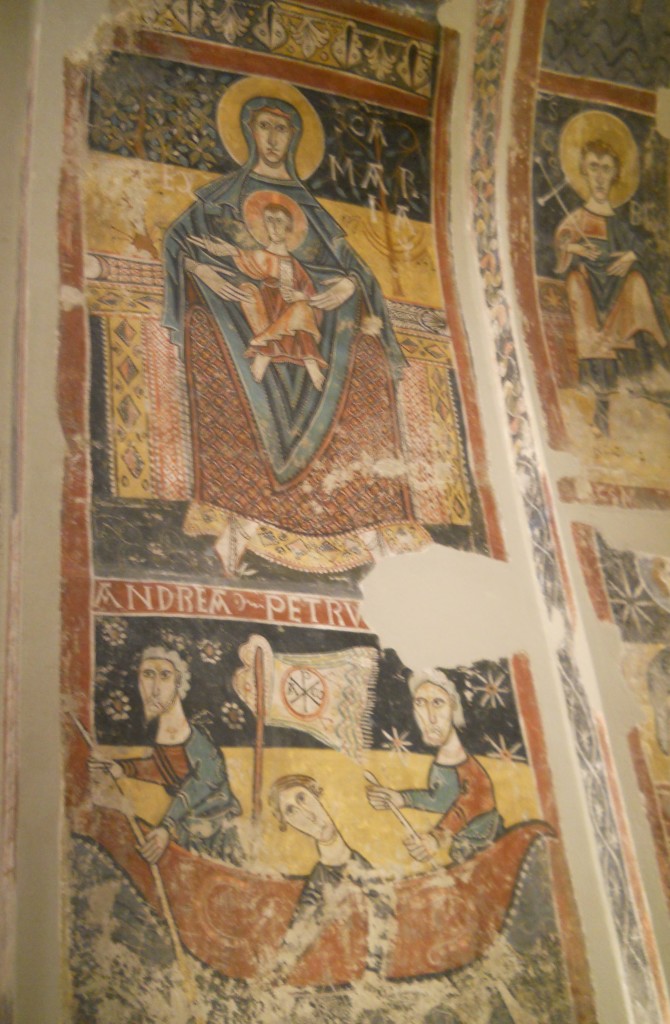

I saw important medieval collections in Barcelona, Vic, and Girona. The MNAC in Barcelona has the largest European collection of Romanesque fresco paintings in the world. Though the term Romanesque usually evokes images of austere gray stone buildings, the installed frescos revealed a far more colorful and luxurious side to this the art of this period, possibly pointing to Mozarabic or Eastern artistic transfer. In particular I was interested in the trompe l’oeil renderings of patterned textiles and animals and how they might relate to, or possibly mimic, the draping of architecture in the Islamic world. Details of textiles are rarely reproduced in studies of Romanesque paintings, which usually concentrate on central motifs such as depictions of Christ in majesty, biblical typologies, or lives of the saints; textiles and animals are usually are treated as marginal subject matter. In person, I could examine the details closely.

When I returned in the fall, I wrote a seminar paper on a group of Castilian frescoes from the chapter house at San Pedro de Arlanza. The frescoes from Arlanza are now split between the MNAC in Barcelona, the Cloisters in New York, and the Fogg Museum in Cambridge. In the paper I explored the works in their original social and historical context. I found that in addition to being given standard iconographical, typological and exegetical interpretations, they could also be regarded as a site of interaction between cultures, political ideologies and religions. The paintings reflect the complex cultural currents of 12th-century Castile, a zone dense and rich with the traces and imprints of Iberian Islamic culture, the increasing importance of pilgrimage routes, the influence of Norman Sicily, and the monasticism of Cluny. The frescos also presented the viewer with a shared international aristocratic visual culture—the visual rhetoric of reconquest and crusade. Like so much 12th-century art, these frescos are a vital mix of exchange, appropriation, and incorporation of cultures.

Finally, the works I saw on this trip also inspired my article “Crusader Chic,” which appeared in Fall 2015 in Lapham’s Quarterly. The article explores the influence of Islamic textiles in the development of the European fashion system after the First Crusade, and was the most viewed article online that Lapham’s had ever published; it has also been translated into French and discussed in the Spanish newspaper El País.