Annie Ewaskio

Grant awarded Fall 2013

I am interested in the complexities arising in a space where buildings, vehicles and other structures permeate lands that were once completely wild. For my thesis paintings, the focus narrowed into a specific dichotomy that incorporated two separate lands into one frame of consciousness: the boreal landscape and the desert city. I had already traveled the American West on my own, but Alaska was a place so far away as to seem mythical. I had to get out there since my work was suffering from having never set foot in the land about which I was painting. The only way I could get there, 4,364 miles away from Brooklyn, was to find grant money somewhere. I applied for a Kossak Travel Grant twice, and the second time my dream to get up north came true – just in time for thesis preparation.

I lined up meetings with many different researchers and policy makers at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. They varied from an interdisciplinary social scientist specializing in environmental and marine policy; the director of the Reindeer Research Program; a geologist studying animal migration patterns and shifting vegetation; and the Scenarios Network for Alaska and Arctic Planning (SNAP). I visited the first woman to finish the Iditarod, and drove out to Chena Hot Springs, where they have built an entire museum out of ice. In Anchorage, I went to the offices of the World Wildlife Fund and met with a specialist who studies polar bear migration and its threatened existence from disappearing sea ice. I drove to Palmer and visited a musk ox farm – arctic animals that originated in the Paleolithic era (Barry Lopez dedicated an entire chapter to their otherworldly qualities in his excellent book, Arctic Dreams). I went to museums in both Anchorage and Fairbanks, and saw a huge range of Arctic art, artifacts, and taxidermy. Probably the most dreamlike experience I had was a twelve-hour train ride through Denali National Park from Anchorage to Fairbanks. The scenery there, in the middle of January, is only something that can be understood in person.

The Arctic is ground zero for climate change. It’s not just that the glaciers and ice caps are melting, causing ocean levels to rise. Melting permafrost is causing entire communities such as Shishmaref to literally fall into the ocean, releasing methane deposits, and creating a series of big problems for the road system. Wildfires are larger and more frequent, changing what kind of trees and shrubs grow. Foliage is growing farther up north in the Arctic tundra. Wildlife populations are shifting in accordance to this and to rising ocean acidity. Polar bears are infiltrate communities, scavenging for food on dry land as they await sea ice formation in order to hunt for seals. Myriad factors are changing very quickly.

Scientists and researchers I interviewed won’t say whether the changes in Alaska are good or bad. They just are. I am interested in the process not just because it is unprecedented in the history of landscape (see Elizabeth Kolbert’s book, The 6th Extinction), but because is infiltrating our psyche. People from all over the world go to Alaska to experience “true wilderness.” Every summer, tourists invade the sea and the land by boat or RV, and travel around in the endless sunshine in order to capture the feeling of being somewhere free, wild, and untouched. In the winter, they come to see the Northern Lights. Visitors are coming to connect with a land that has, for thousands of years, sustained relatively small groups of people not just physically but spiritually.

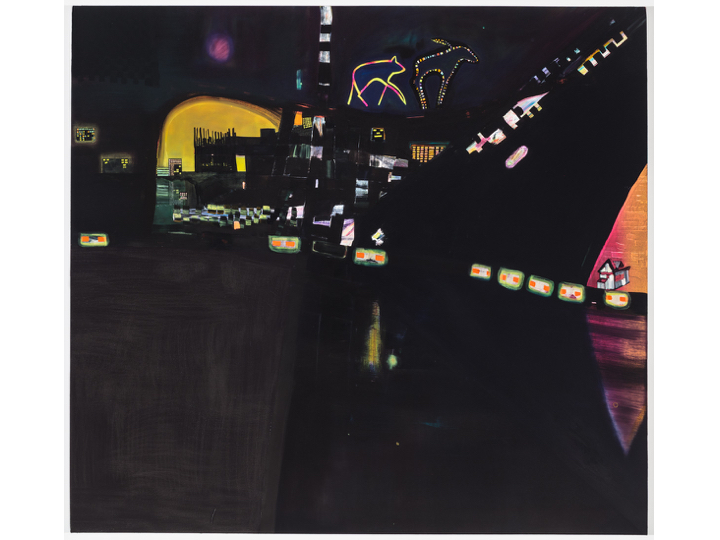

My paintings are still experiencing the aftershocks of having been on such an extreme trip. Because I was there in January, everything was dark all the time, as my black paintings seem to reflect. I became more and more fascinated by the idea of tiny little huts out in the middle of nowhere, housing warmth and light and activity. Visual cues pop up in my paintings – a snow-cat here, an arctic fox there, and fir trees galore. The knowledge I have now, of this perpetually in-flux land up in our northernmost part of the United States, influences the awkward, receding and coming-forward moments in my paintings’ spatial organizations.

The Kossak committee’s confidence in my research helped fuel the support I am fortunate to receive from places outside of Hunter. As I had always hoped, the trip served as a springboard for further Arctic travel. In summer 2016 I am off to Svalbard, off the northern coast of Norway, to sail with The Arctic Circle Residency. The Jerome Foundation generously awarded me a travel grant for this adventure.

I owe many thanks to Drew Beattie and the rest of the Kossak committee: Joel Carreiro, Gabriele Evertz, Valerie Jaudon, Jeff Mongrain, Howard Singerman, and Tom Weaver. In particular, I would like to thank Evelyn Kossak once again for her incredibly generous and thoughtful contributions. I am happy I had the chance to thank her in person, and I will thank her again here. Thank you!