Andy Van Dinh

Grant awarded Spring 2016

Vietnam Andy Van Dinh from Andy Van Dinh on Vimeo.

website: http://www.andyvandinh.com/

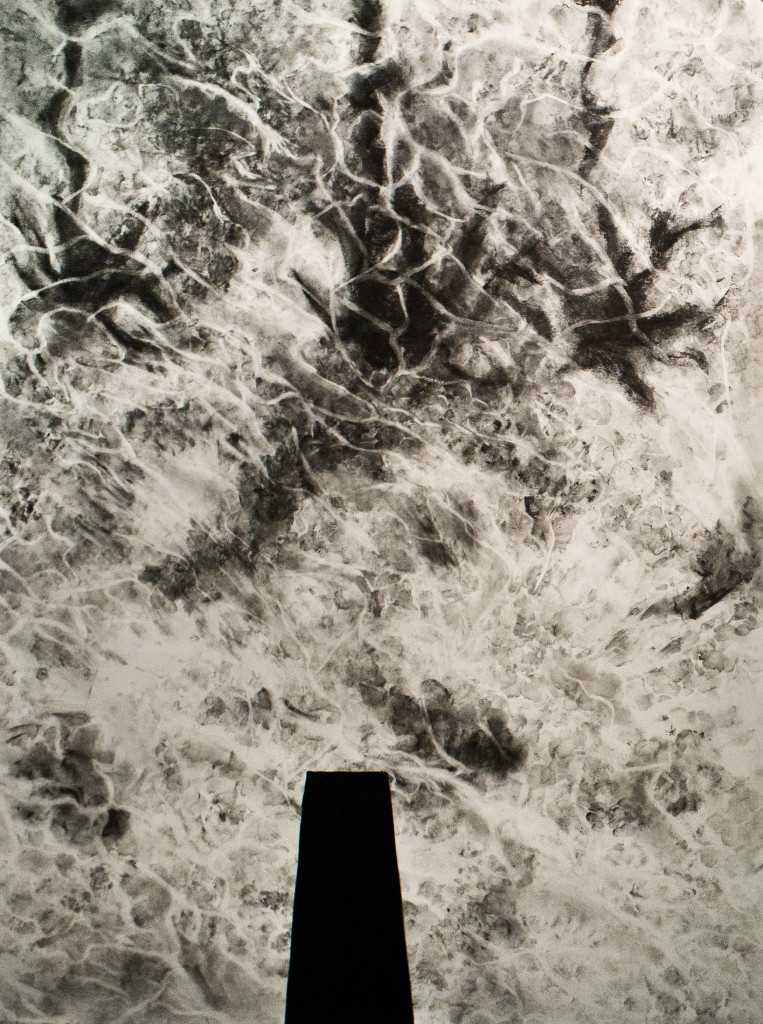

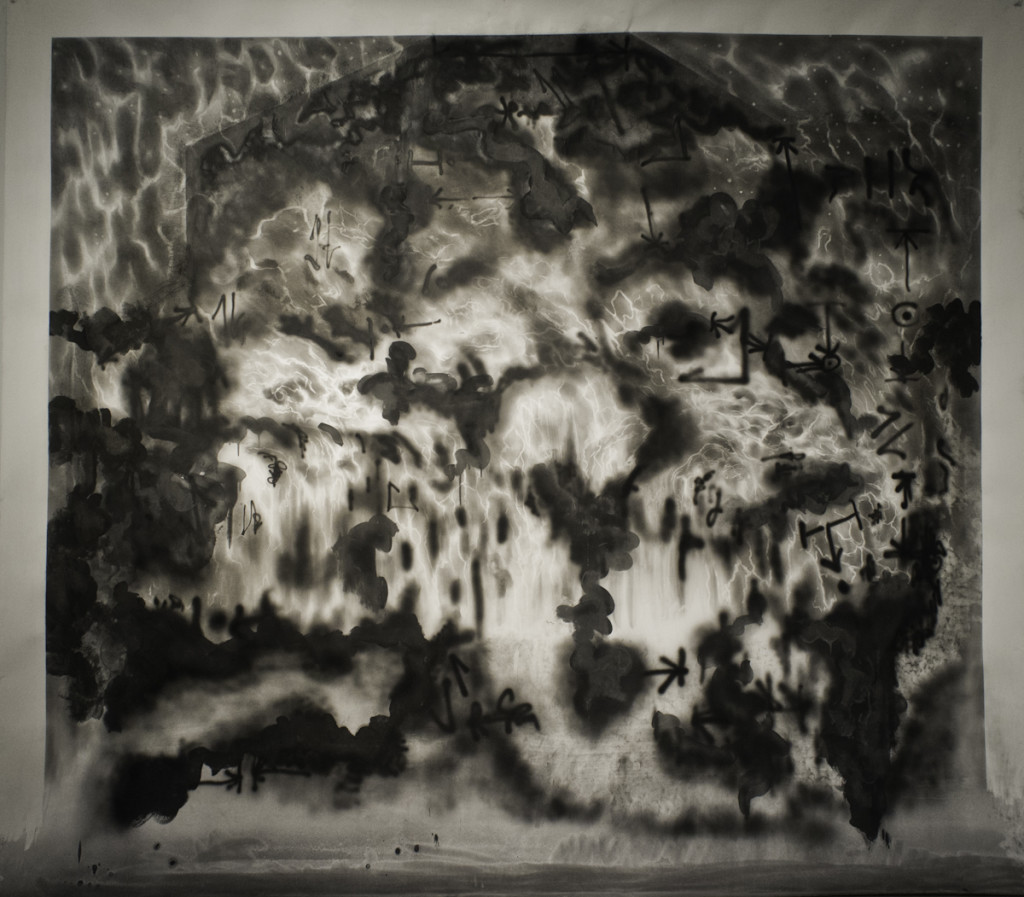

If You Don’t Know Now You Know

Through the Kossak grant I was able to travel to Vietnam, a place I am culturally connected to through my parents but I have never been there before. My mom came with me and the last time she was there was when she was running away from the Vietnam War, and eventually found herself in Canada. This trip helped me answer so questions I’ve had about the Motherland, and some background information about my family. The trip helped me realize why I am the way I am today.

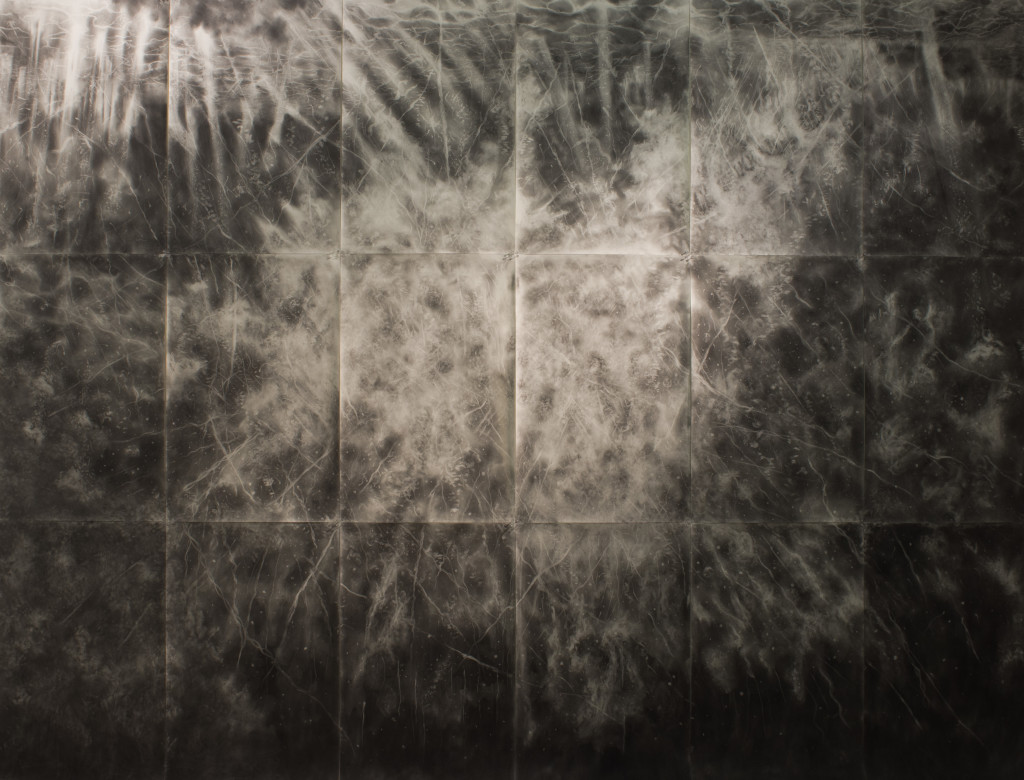

I belong in North America but I don’t exactly fit in. I fit in Vietnam but I don’t belong there. This state of limbo or an “in-between” of a home and an un-homed nation has resulted in an identity crisis for myself and many of my friends of color. What is my relationship between self and place? How has living in Canada changed how positively or negatively I feel about my ethnicity?

I grew up in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. It’s a hockey city, famous for it’s annual outdoor Western themed carnival called The Stampede. They go as far as self proclaiming it as the ‘Greatest outdoor show in the world,’ but it’s just a typical carnival decorated with myths of the west. As a Vietnamese drowning in a sea of fake cowboys if I tried to fit in I just stuck out even more. I was the stinky kid in school just because I brought vietnamese food for lunch (it doesn’t even smell bad). I saw my ethnicity as a curse and I spent majority of my life trying to be white. I thought being considered white washed was a compliment. I refused anything that made me seem more Asian (whatever that really means). However, I could only handle so much whiteness, and I started to fight assimilation. I realized that trying to be white was some kind of neo colonialism. Colonizing of the mind. So I refused to attend the Stampede, I refused to like hockey, and I refused to move my arms in Y.M.C.A formation every time that Village People song played. I was done with whiteness because it made me hate my ethnicity and who I am. I am done being apologetic for who I am.

At a young age I gravitated towards Hip Hop. Run DMC making a cameo on the Reading Rainbow and wearing laceless Adidas shoes was the very beginning for me. Wu-tang Clan appropriating Shaolin Wushu was a game changer, and Nas’s album, Illmatic, did more for me than anything Keith Urban has ever made. I was a hip hop head in a country music lovin’ conservative oil & gas city. I wasn’t about driving in a pickup truck dressed in tight jeans, spurs on my city boots, and blasting the Dixie Chicks. Nah, you could catch me with my three other Asian homies in a lowrider Oldsmobile (not an actual lowrider, the suspension was busted so the ride swung low), dressed in all black, clinging onto every word Jay-Z said on the Black Album.

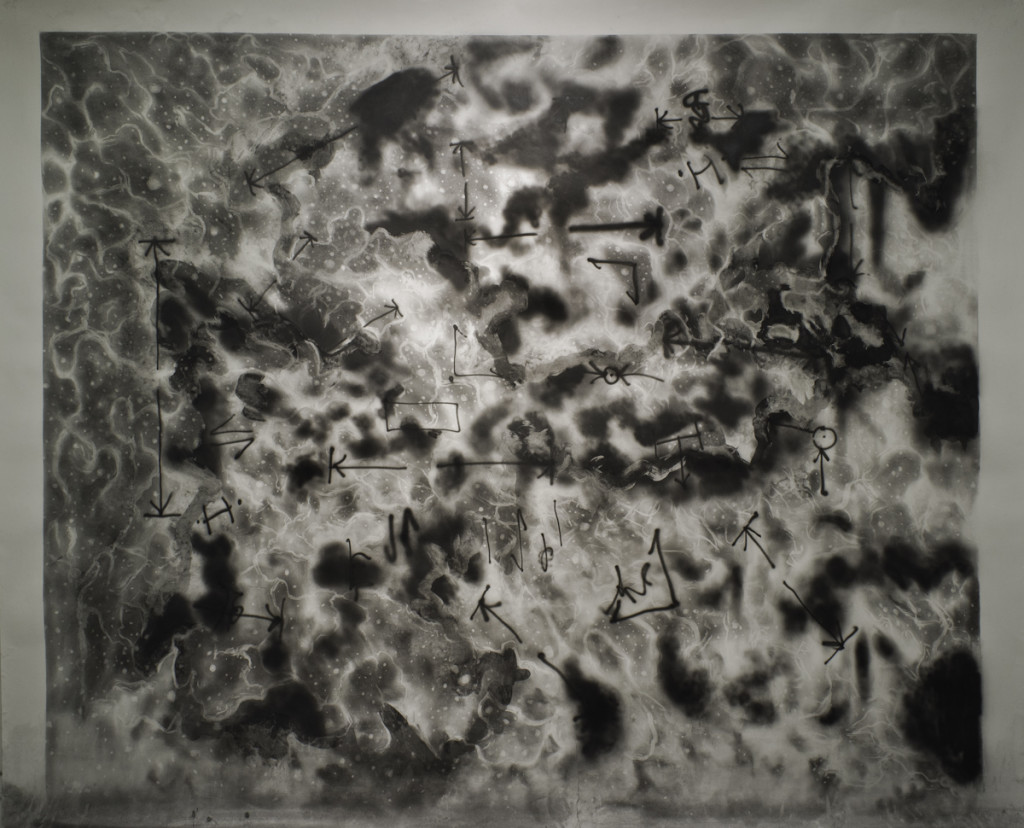

I used what I thought was oppositional cultures to construct my identity, but I didn’t realize that all of it was an expected reaction. I was still being played by the system. I was too focussed on how I’m not white rather than understanding what it means to be a Vietnamese in America. I wasn’t able to step out of the box and analyze the forces being played on me. I forgot about my roots and where I came from. I was a blank slate for anyone else to write anything for me.

The Diaspora The Displaced

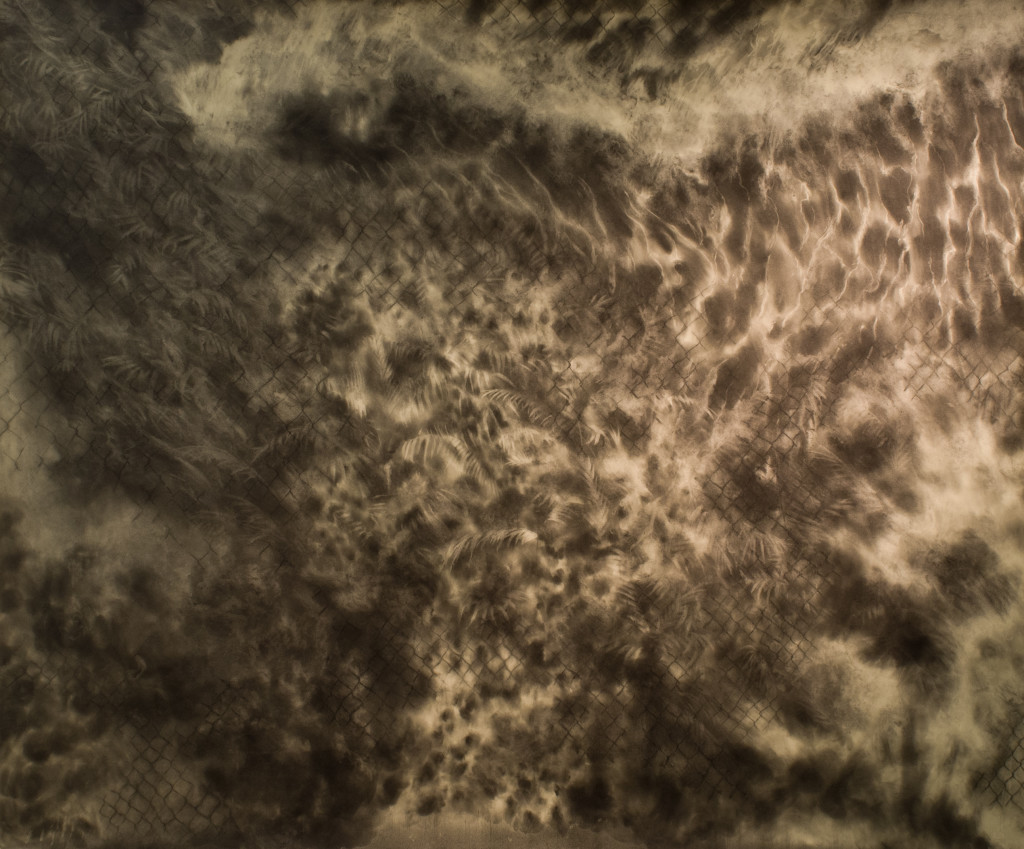

Majority of what I know about Vietnam comes from war movies and what I briefly learned in Social Studies. It’s as if I’ve been sold a false narrative. A false beginning and ending; nothing before and nothing after. Vietnam trapped in a singular identity, which my life has evolved around.

Growing up, whenever I would take life for granted my parents would tell me stories about the chaos of the Vietnam War and their escape by crossing the Pacific Ocean and eventually finding their way to Canada. These stories at times were hard to digest. They consisted of war casualties, being inside a boat overpacked with sea-sick passengers, eating the weirdest things to survive, being engulfed by 50 foot waves, and being rejected from multiple borders which meant prolonging death at sea. They always brought me back down to earth, but there’s always been a sadness lingering over my family. I have inherited the traumas of wars and natural disasters through collective memory. I am the distillation of this cultural sadness, the haunting history, and I recognize the aftermath in the way I’ve engaged with the world, my methods of adapting, the clothes I’ve worn, and even how I have loved. This feeling of displacement is hard to explain. there’s this measurable distance between where I am now and Vietnam, and there is also an intangible distance between my Vietnamese roots and the cultures I’ve assimilated in. I belong in North America but I don’t necessarily fit in. I may fit in Vietnam but I do not belong there. I am a stranger to both places, here and there; stuck in limbo.

With the help of the Kossak funding I’ve been able to shorten the distance and feel more comfortable with myself, my history, my ethnicity. I understand now to resist the narratives being forced upon me, resist the ones pushing me into the margins. I too can be my complete self on this shared land.

Thank you Kossak

-Andy Van Dinh